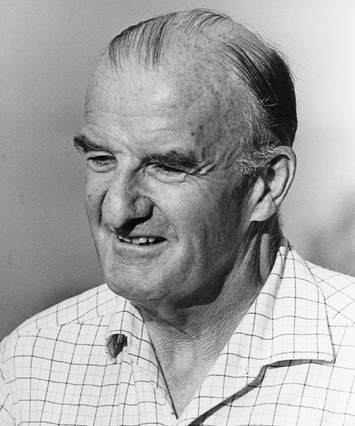

Businessman Eric Priestley introduced Roger Hicks at this Lunch meeting: "The heading for this luncheon, as the first in a series of luncheons, is ‘Thinking Ahead’, as you have seen on the card. The need for that is paramount today in this fast-moving world in which we all live and it is often difficult to keep up to date with things."

Roger Hicks:

I think it is just about a year ago that some of you here were at a lunch where Rajmohan Gandhi spoke - the grandson of Mahatma Gandhi. He is also a very close friend of our speaker today, Mr Roger Hicks, whom I am very glad to welcome here in Sheffield to speak. Rajmohan Gandhi spoke to us in Sheffield and I don’t know whether we were thinking ahead at the time, but it is certain that we shall hear from Mr Hicks as to what he is doing in Indian now at this very crucial time.

Today we are very fortunate in having Mr Roger Hicks here with us. He is a graduate of Oxford University. He first went to India in 1928, when he lectured in history at Madras University. Since then he has known personally virtually all the leaders of India. He was a friend of Mahatma Gandhi and stayed with him during the difficult days of a controversy over there. He took messages from Gandhi to the Viceroy. He is the only Englishman in those days to be invited to the working committee of the Congress. Mr Hicks also knows most of the post-war Prime Ministers in Asia - Pakistan, Burma and Ceylon.

Roger Hicks: Mr Chairman, Gentlemen - would you like to turn your chairs and give me more courage by seeing your faces? I think that is more comfortable for all of us.

The title of these talks, ‘Thinking Ahead’, is, I think, a very good title, because if we fail to think ahead we may not be in a position to think at all. This world is moving at a very fast rate and the thinking of ten years ago does not apply to today. Perhaps nowhere is that more true than in Africa and in Asia, where Britain left those countries and things have not generally taken the course which most people expected.

Coming down in the train yesterday, I read a review of two new books that have come out. Important books. One called ‘The New States of Asia’ by Michael Brecker and the other ‘Nationality and Wealth’ by a man called Luard The review says, ‘10 years ago we thought of Asia and Africa as continents at the end of colonialism. Today we are beginning to realise that their emancipation was really the opening of a new age in world history. When Mr Brecker says that Asia is the Achilles heel of a future world society, he is only underlining the shift of focus from the Atlantic to the Pacific, of which we are increasingly aware.’

Now we did a good job in many ways in India. We left behind in India a trained Indian civil service, of Indians. I had to lecture during the war sometimes in America when certain people were trying to prove to the Americans that the British were a great imperialistic power exercising tyranny over India. I pointed out in my lectures that there were fewer Englishmen in the Indian civil service at that time than there were servants in the Waldorf Astoria hotel. We did not rule by tyranny there. We left behind also an Indian Army, with Indian officers. Yet in spite of that, no sooner had we left the country than half a million people butchered each other. India and Pakistan had to divide. They couldn’t get along together. Since that time there have been increasing divisions. Today East and West Pakistan are grievously divided and many people feel that, when Nehru dies, India may fall into fragments.

I came back a few months ago with a very senior Indian official and I asked him the usual question ‘What is going to happen after Nehru?’ He said, ‘It is going to be worse than the French Revolution.’ Whether that is true or not I don’t know. I hope it isn’t. It may not be. But the thing we did not leave behind in India, and we did not leave behind in Africa, was the art of people living together. We did not teach them how to live together. It happened fairly slowly in India but in Africa we have seen the speed of what happens after we leave. How quickly others go in to fill the void which we left.

What is Mr Chou En-Lai doing in Africa today? Has Zanzibar become the Cuba of Africa? What’s his game? What’s happening there?

I thought we would discuss a little of what Mr Chou En-Lai did in India and Ceylon where I happened to follow him about, so that we can learn something of what he may be trying to do in Africa and in other parts of the world.

In October 1960, and again in October 1962, China invaded India. The latter was far more serious. They routed the Indian army in three weeks and then to everybody’s surprise called a ceasefire. We cannot go into the reasons for that now - I believe there are 9 good reasons, and I believe she had to call a ceasefire. But she defeated the Indian army. Assam, where Britain has £5 hundred million worth of assets, was very nearly overrun. The Times called it ‘a border issue with other factors superimposed’. Now it was not that. It was a planned part of an expansionist move. Unless we understand and realise that we shall get Africa wrong, we shall get Asia wrong, and we shall lose out.

I happened to be in the Prime Minister’s house in Delhi, in November 1954 when a telephone call came from Krishna Menon in Geneva. He said that he had Mr Chou En-Lai with him and would PM Nehru kindly put off his visit to Kashmir as he wished to bring Chou En-Lai with him to India to confer with the PM. They conferred, and at the end of their 4-5 days together they confirmed the five principles of co-existence. They talked of the 2,000 years of Chinese-Indian friendship and how they were brothers together. No sooner had Chou En-Lai left Delhi than a friend asked me to come and see him.

This friend was an underground communist leader. I met him some months earlier and got to know him and he lost his fervour for the communist ideology. He told me he discovered he was a democrat by conviction and a communist through bitterness. But because Nehru had not taken him into the central Cabinet he decided to make his state communist. He was the only man whom Chou En-Lai sent for. He had had no touch with the communist party in India - like most of the effective communists they worked underground. He asked me to come and see him and he said, ‘Would you like to know what Chou En-Lai and I talked about?’ So I made a good English understatement - I said it would not be without interest - and he told me what it was.

First and foremost he said the Chinese are coming over the Himalayas and going to invade India. This was in 1954, when he and Nehru were issuing their eternal brotherhood statements. He said I am to take religious plays to the foothills of the Himalayas where they are coming. We are to take the old religious dramas, which India trusts, and to give them a slight twist, so the landlord is a villain, the peasant is a hero, and the god backs the peasant.

Then I am to buy men of the press to write articles about the enduring friendship of China and India and be willing to take China’s side if any controversy comes. I am to further the printing presses which have already been supplied in certain parts and direct what they print. I am also in charge of 1,000 study groups, none of which bear the communist name.

That is actually what Chou En-Lai was doing in India, under the guise of other things.

I then went down to Ceylon. He happened to have gone there ahead of me. I met the Governor-General whom I had known for many years. He said, ‘When I heard that Chou En-Lai was coming I remembered the talks we had had and I decided to see for myself what a man with an ideology really did. So I met him when he arrived and I spent ten and a half hours in his presence during the time he was in Ceylon - an unusual amount of time for a G-G. During that time he never made one negative remark about anything. He was full of praise. He insisted upon spending a lot of his time visiting Buddhist temples. He gave a personal gift of Rs. 30,000 to the Buddhist priests for the furtherance of their Buddhist work.’ So that when he left the Buddhist priests came to the G-G and said, ‘Why do you people say that communists are against religion? We have never had a visitor so appreciative of our religion or so devout.’

‘That,’ said the G-G, ‘is ideology.’

At that time China had invaded Tibet and the stories of their cruelty to the Tibetans, fellow-Buddhists with the Ceylonese, had begun to reach Ceylon and so Chou En-Lai had to give a counter-measure. He went back to China and a remarkable thing happened. They suddenly discovered a holy relic of the Buddha which no one had ever heard of before. Nothing less than a tooth of the Buddha. So friends of China in Ceylon arranged for an invitation and the tooth was brought in tremendous state all the way round Ceylon. I was there at the time, and remember being held up one day while the cavalcade went by. The idea was to get the Buddhist priests to worship this tooth, to give it reverence, again to show how devout China was and how she cared for the Buddha.

But fortunately there were some visiting priests from Burma who showed up there again and the Chinese were not very successful at that time. But that is the kind of way in which they were preparing the ground for future work.

They had visitors down from the Assam and Bengal hills. They said ‘The Chinese have indoctrinated the people here from right to left, all the way. Beautiful glossy magazines, showing the prosperity of the Chinese peasants, promises that they would own the estates when the Chinese come and also that their national hero SC Bose was not killed in the war but would come back and lead them.’ I could tell you story after story of people there who had met Chou En Lai and his hordes and been part of the preparing force for China to advance there.

In 1954 maps were issued in Peking which are used in schoolbooks in China today, showing the Chinese Empire. It incorporates North-East India, Burma, Singapore, Malaya, Vietnam and all those portions of Asia, as well as parts of Siberia and Mongolia. There is no doubt whatsoever, I believe, that China has her eyes on getting back what she regards as her empire.

But, remember China defeated the Indian army in three weeks. Asia took note. Where could she turn to? Laos had been guaranteed by the UN, the USA and the UK. The communists made a mess of that - all those guarantees meant nothing. Oceania had been promised self-determination and handed over to Indonesia. Vietnam - the blue-eyed boy of America, as Diem told me personally, could have all the aid she wanted from America, she only had to ask for it - abandoned and coups d’etat and murders. Where do they turn to? Where does Asia turn to? Guarantees were no good. The aid was no good. The policy of appeasement and a blind eye was no good.

The day after the Chinese came over the border in India the senior cabinet minister and the present acting PM, Nanda, phoned up the man who spoke here last year - Rajmohan Gandhi. They said to him, ‘For two years you have been telling us in the cabinet what was going to happen and we would not believe you. It has now happened. Your information was better than ours. Will you come and tell us now what you feel should be done?’

With special thanks to Ginny Wigan for her transcription, and Lyria Normington for her editing and correction.

English