Chris Channer talks with Amanda Clements about a lifetime using theatre to make a difference.

Chris Channer is a sprightly, 94-year-old retired dancer and actor. Her South London home is full of stage memorabilia and family treasures.

As a struggling actress just after World War II, she says she was rather ‘a wayward girl’. It was the prospect of free food that got her to the Westminster Theatre that evening in 1946, as ‘she was rather hungry’. It was that night that her life changed.

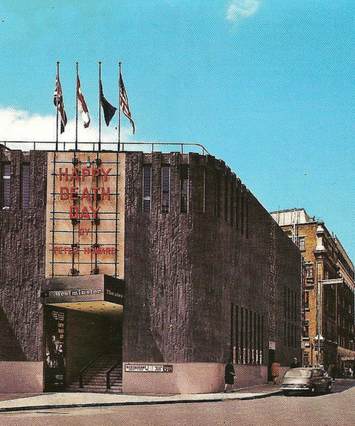

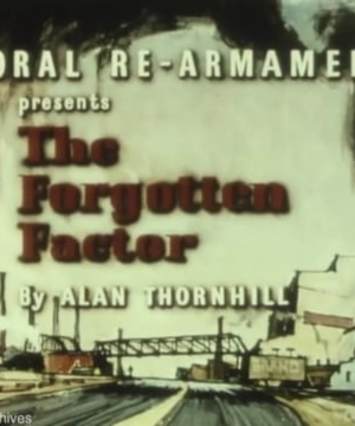

The play Chris had gone to see – The Forgotten Factor – was the first play staged by Moral Re-Armament (now Initiatives of Change) after it bought the Westminster Theatre in 1946. Chris’s parents were members of the group of businesspeople who raised the money to buy the theatre as a memorial to MRA servicemen who had died in the war. The money had arrived in 2,857 gifts, mostly small.

The play looked at industrial relations through the story of two families on either side of an industrial dispute, and suggested that change in the world had to start in the individual. Chris was struck by the good-looking American actors. When she met them after the play, she found them ‘outgoing and straightforward’. ‘My life was in a mess and in need of a good clear out,’ she says. Professionally, she was going through a difficult time, with a challenging role. ‘For the first time ever I prayed about a part that I had to play.’

When she was invited to go to the MRA conference centre in Caux, Switzerland, she was flattered but unsure. ‘I wasn’t conference material and I only read the theatre critics, never the front pages of newspapers.’ But she had 12 free days between the end of her ballet engagement and the contract she had signed for the Edinburgh Festival; her parents paid for her to go, as she was ‘absolutely skint’.

Once there, she only went to one meeting. At it she heard Irène Laure, a French socialist leader and a member of the Resistance in Marseilles during World War II, apologise to the Germans present for her hatred of them. ‘It was an electrifying experience,’ she remembers. ‘I was deeply impacted because it was not just words but real change.’ She spent most of the rest of her time in the Caux theatre, observing ‘how they used theatre to carry the message’.

During this time, two older actresses asked her to help with an MRA production. She said she would after she had worked out her contract for the Edinburgh Festival. One of them said: ‘Don’t you think that’s rather a cheap way of looking at it – saying to God, “I’ll do your work, but in my time”?’ Chris knew in her heart she was at a crossroads. She went up the mountain for some peace ‘to listen to the voice within’.

It was an epiphany. ‘It was a profound opportunity to make a change; a call to action.’ The ‘whole world’ was represented at Caux, and ‘there was so much healing needed’. She wrote pulling out of her contract, and received a letter back from the company director saying her action was crazy. But a week later he wrote again, ‘If you believe you are doing the right thing, I will find somebody to replace you.’

Chris went on to tour with MRA productions in many countries – she met her husband, Dick, playing siblings in one travelling show. ‘It was part of our life to reach out to people. Wherever you were you would be part of the community you found yourself in.’

Until it was sold in 1998, Chris both appeared in productions at the Westminster Theatre and helped to run it. It gained a reputation as a professional theatre which viewed contemporary issues ‘through the lens of faith and moral values’ and aimed to give audiences new will to address the problems in their lives and communities.

Audiences used to come in coachloads from all over the country. Its schools programme, which ran from 1967 to 1990, brought in 300 children a day at its height. The audiences could stay after some performances to talk to the cast. This disrupted standard theatre conventions and was ‘groundbreaking’ for both audience and actors.

Chris has maintained contact with many of the young actors who took part in productions at the theatre. She talks of one, now at the top of his profession and a pioneer of Black theatre, who wrote to her: ‘You’ll never know what you did for me.’

Looking back to her experience at Caux, all those years ago, Chris says that it challenged her to ‘clean up her own life and help give meaning to others: I wouldn’t have had anything to say to anybody if I had stayed as I was’. Her experience gave her courage to act on her beliefs. ‘I grasped the chance to play a part in changing the way things were in the world by the way I lived.’

English