by Michael Paul Williams

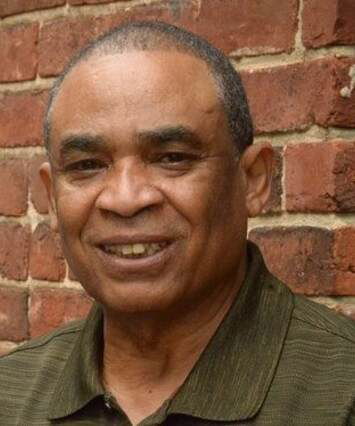

Rev. Sylvester "Tee" Turner was one of the unsung individuals whose insistent work helped tug Richmond's largely hidden history of racism out of the shadows.

Whether striving to build a slavery museum in Shockoe Bottom, co-leading a groundbreaking Unity Walk through Richmond's racial history, mentoring younger community leaders or traveling the globe to apply lessons learned in his hometown, "He lived what he said he believed," said his longtime friend, the Rev. Benjamin Campbell.

"He wasn't a flashy person, he was just a faithful person," Campbell said, adding: "He would take on really rugged racial stuff, but his kindness was a magic sauce."

Turner, 74, the pastor of Pilgrim Baptist Church, died Sunday. He is being mourned as a man who worked tirelessly but without fanfare to mold better people and build better communities.

“He wanted to help everyone find healing in their lives and be effective in their communities," said Rob Corcoran, who in the early 1990s founded Hope in the Cities, a flagship Richmond-based program of the global Initiatives of Change (IofC), to promote honest conversations around race. Turner, whom he described in a tribute as "a founding pillar of the Hope in the Cities movement," had “an unwavering commitment to truth telling, to justice, to healing and reconciliation."

He also had a passion for mentoring.

"Tee did the unspoken hero work of reaching out to young Black folk like myself, to pour into us and give us wise counsel, to put us in position and in rooms that spoke to who we might become," said Duron Chavis, director of Happily Natural Day. "He’d take you to lunch and give you the game, insight into this community work, but also on fatherhood, being a husband — he was a one of one. We need more people like Tee who show up when nobody is looking."

Turner, the former head of Peter Paul Development Center in Richmond’s East End,wasn't one to seek headlines. But the story of Richmond's passage from denial to racial dialogue would have been underwritten without his contribution.

According to Corcoran, Turner — who would travel the world with him on behalf of IofC —described his approach to reconciliation as a process of acknowledgment and apology, forgiveness and accountability, and working together.

Turner grew up in the public housing community of Gilpin Court, left to join the Air Force and became an ordained minister in Austin, Texas, before returning to Richmond "because he wanted to serve the community he came from," said Corcoran, who now lives in Austin, in an interview.

Turner met Campbell, then pastoral director at Richmond Hill, while heading Peter Paul Development Center. In June 1993, they would lead Hope in the Cities' Unity Walk, a groundbreaking pedestrian tour of Richmond's history of racism and slavery.

Turner's efforts on behalf of Hope in the Cities and Initiatives of Change took him to South Africa, Nigeria, Cameroon, Kenya, Nepal, Indonesia, Australia and Canada, among other places.

“He was well-known in our international network," said Corcoran, former U.S. national director for IofC. But he also lauded Turner's work in LaGrange, Georgia, the site of the 1940 lynching of Austin Callaway, who'd been charged with the attempted assault of a white woman. Calloway was taken out of his jail cell by a group of white men, driven miles away, and shot and left for dead.

More than seven decades after the lynching, about a half-dozen people from LaGrange took part in Initiatives of Change's Trustbuilding Fellowship out of Richmond Hill. They returned home to Georgia to start their own Trustbuilding program.

"Tee was constantly communicating with them," Corcoran recalled. In 2017, LaGrange Police Chief Louis Dekmar made national news in apologizing for the lynching.

Turner and Tanya Gonzalez, now the executive director at Sacred Heart Center, got to know each other as 2003 classmates in Leadership Metro Richmond.

"In a way, he was like a spiritual advisor to me," she said.

“I was young and just starting my community work in Richmond at that point, and he kindof took me under his wing," Gonzalez recalled. Turner not only strengthened her understanding of Richmond; he encouraged her to connect with Hope in the Cities.

She'd ultimately volunteer with the organization, traveling to Colombia and to the Caux,Switzerland, center of Initiatives of Change, growing her international network and resources.

Gonzalez and Turner, a former member of the Richmond Slave Trail Commission, would take walks along what is now called the Trail of the Enslaved. On that riverside path where shackled Africans were marched into Shockoe Bottom, Turner and Gonzalez would search for common ground and shared humanity between the Black and Latino communities.

"He'd reach out every few months and say, 'Tanya, it's time for us to go to lunch,'" she recalled. "We created Black and Brown solidarity on a personal level. He had his group of people he was supporting — quietly, gently, but fiercely."

Turner is survived by his wife, Myrtle J. Turner, of Richmond; a daughter, Tressie Edwards of Virginia Beach; and a son, Stanley Ware of Henrico.

Michael Paul Williams

English