(Note: the correct spelling of his name is N'komo, but we are using Nkomo in this website because almost all published material uses the incorrect spelling.)

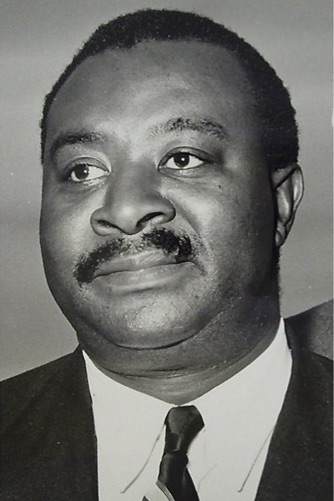

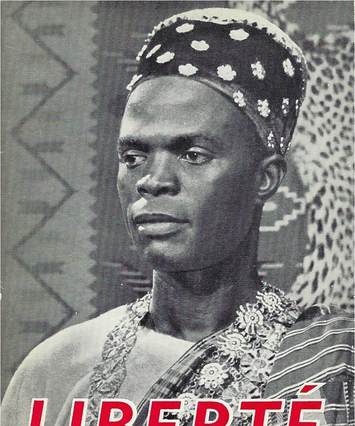

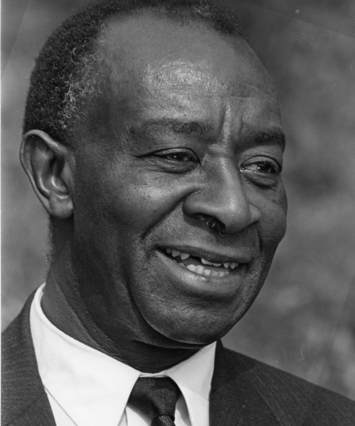

William Frederick Nkomo was born in the rural village of Makapanstad, north of Pretoria in 1915, the fifth child in a family of eleven. He was the son of a Methodist minister, Abraham Nkomo. After matriculating at the Healdtown Institute near Fort Beaufort in the Eastern Cape in 1937, he studied for a B Sc degree at the South African Native College (Fort Hare). He also obtained his BA degree from the University of South Africa (UNISA) followed by a degree in medicine at the University of the Witwatersrand, where he was the first African to be elected to the Students' Representative Council.

Despite years of brilliant study, he was turned down at all the hospitals where he applied for work. Bitterly frustrated, he joined the African National Congress (ANC) and aggressively campaigned for Black people's rights.

In 1944 Nkomo was one of the founders of the African National Congress Youth League. He became its first president. 'I did not at that time,' he wrote, 'struggle for a united Africa in which all races could live together happily but I visualized an Africa in which only the African got the right to rule. I felt we had to organize the African masses to rise against their foreign oppressors to the extent of driving them into the seas. To me the slogan ‘African for the Africans’ meant black domination for Africa.'

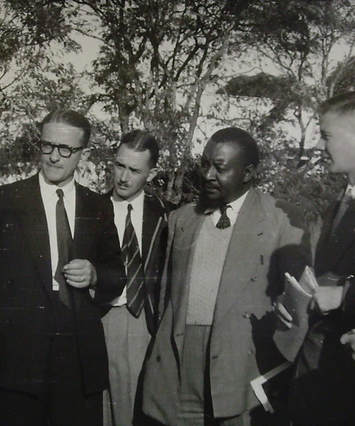

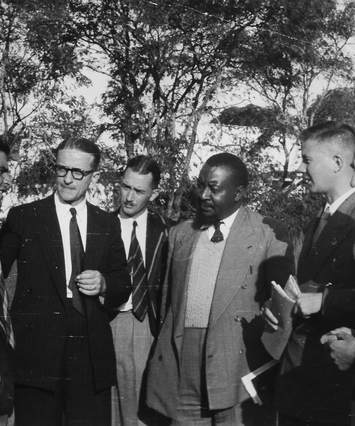

At about this point, four Afrikaner students visited him from the all-white University of Pretoria. To his utter surprise, they apologized for their former arrogance towards black people, explaining that they believed this attitude resulted in discrimination and violence between races. These statements intrigued Nkomo and he accepted an invitation to a Moral Re-Armament conference in Lusaka, Northern Rhodesia (Zambia), to discover what could induce rabid Afrikaner Nationalists to change their attitudes so drastically.

The conference was a turning point in Nkomo’s life. He said, 'There I saw white men change and black men change. I too decided to change.'

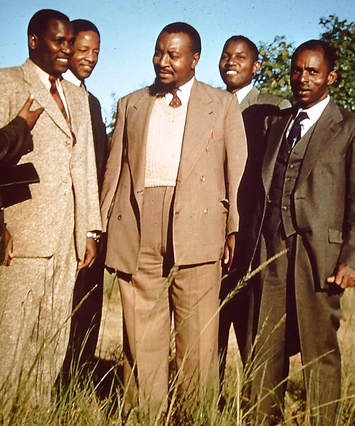

Opposition came his way from both black and white South Africans who regarded him with deep suspicion and mistrust. His home was set alight. Yet, he never again took up violence and came to be trusted by people of all races.

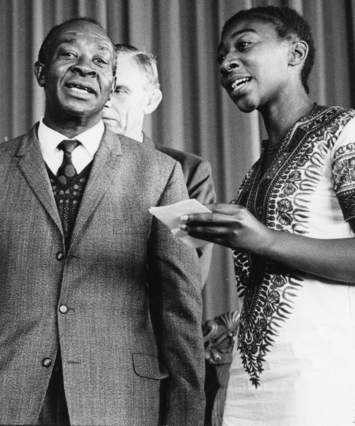

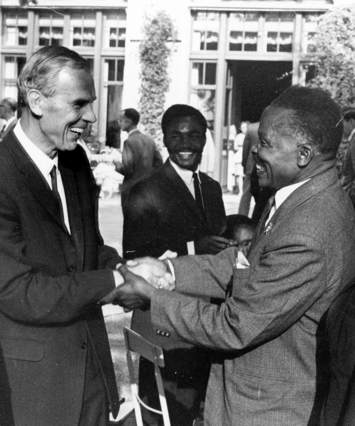

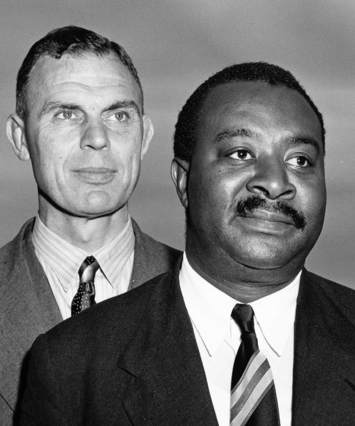

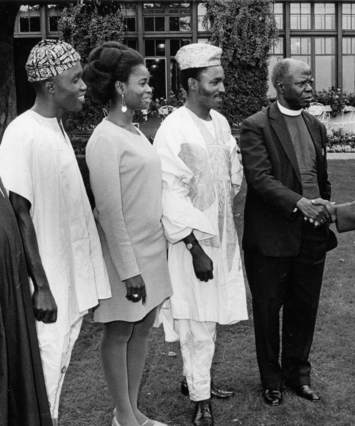

In 1961 he was one of three Africans chosen to meet the late Dag Hammarsjőld, then Secretary General of the United Nations. He was the first African to be elected President of the South African Institute of Race Relations. He was the first African in the country to form, with his son, Abraham, a father-son medical partnership. Until his death Nkomo served as the Trustee of the Bantu Welfare Trust, which aimed to improve the lot of urban Africans and promote co-operation between black and white South Africans.

The people of Atteridgeville, where he lived, honoured him by celebrating a William Nkomo Day and naming a school after him. 'He always had his facts straight and he never pulled any punches,' said a friend. A grateful patient of his said, 'He was the only doctor I knew who never sent an account.'

Not very long before his death he was hit without reason by a white traffic policeman, which resulted in blindness in one eye. In court the case was discharged. Nkomo was overwhelmed by bitterness. 'I thought that maybe we had turned to God for solutions often enough,' he recalled. 'Maybe we should take this to blood. But then God said to me very clearly: 'Don't hold a people responsible for the action of one individual.' That gave me the strength and will to overcome my bitterness and go on.'

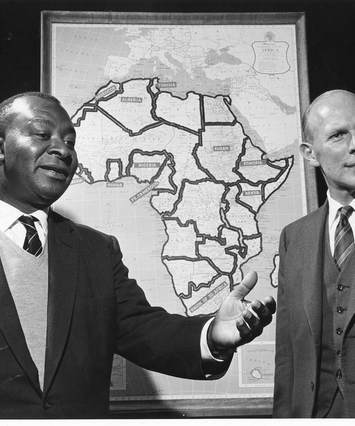

'I am no less a revolutionary because I listen to God, but I have renounced the path of violence, of hatred. I hate passionately the things that divide men and I’m fighting with greater passion for things that will unite us above every affiliation, above race, above colour,' Nkomo said, speaking at an international conference at the MRA centre in Switzerland. 'I’m fighting for a hate-free, fear-free, greed-free continent peopled by free men and women,' he said.

In Pretoria, on March 26, 1972, Nkomo died of cardiac arrest. Ten thousand people attended his funeral. He was buried next to his wife, Susan, at the Rebecca Street Cemetery in Pretoria west. They had five children.

A 26 minute documentary film 'A Man for All People' was made about the life of Dr William F. Nkomo.